Health illiteracy in urological patients

In health care, having a patient optimally informed is of the utmost importance. Well-informed patients take better care of themselves, tend to have fewer complications, have better treatment outcomes and feel more in charge of their own health.

Today, however, when there is an increasing amount of our information presented to our patients such as printed brochures and websites, problems arise: the health standard of millions of people in Europe who are unable to read and write at a proper level will further fall behind.

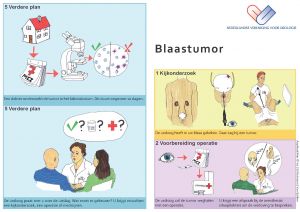

Part of a bladder cancer patient information leaflet for illiterate patients of the Dutch Urological Association (NVU)

Illiteracy is the inability to read or write and in the Netherlands alone, 250,000 men and women out of a population of 17 million are identified as illiterates. Even more people – 2.5 million over the age of 18 – are considered to have low literacy skills: they have trouble fulfilling tasks most of us think are easy such as reading a menu, writing an email or finding out a train schedule. Most of these people lack other abilities as well, such as digital skills and mathematical calculation. Almost all of them should be regarded as being ‘health illiterate’, meaning they lack knowledge, motivation and competencies to access, understand, appraise, and apply health information to make judgments and take decisions in everyday life concerning healthcare, disease prevention and health promotion, or to maintain or improve quality of life.

If these figures surprised you they are worse for most of the other European countries. In the “Comparative Report on Health Literacy in Eight EU Member States” (2012), health Illiteracy was investigated in Austria, Bulgaria, Germany (North Rhine-Westphalia), Greece, Ireland, Netherlands, Poland, and Spain, showing inadequate to problematic health literacy in 28.7% of the study participants in the Netherlands and up to 62.1% in Bulgaria (mean 47.6%). Unfortunately, these numbers are unlikely to change within a short time.

Obviously this has consequences on issues regarding health promotion and disease prevention. In case people are unable to access, understand, interpret and judge the relevance of information on risk factors or health issues, undoubtedly this will affect their health. For urological patients: will they act on alarm symptoms appropriately? Know the effects of smoking on the risk of bladder cancer? Or erectile dysfunction? Will they be able to outweigh the pros and cons of PSA testing? To use decision aids once urological disease is diagnosed? Will they really be able to participate in shared decision-making?

Patients with low health literacy skills often miss their appointments. Or show up on the wrong date or location. They visit the hospital more often than literate people do, as they don’t understand the given information very well, or follow instructions wrongly. Please note that words that seem so clear to us, like ‘impotence’ or ‘incontinence’ are only understood by a minority of people. But illiteracy also results to, for example, not stopping anticoagulants before an operation or having eaten while not allowed to, leading to the cancelation of procedures. In the Netherlands, it is estimated that these issues result in extra costs of 127 million euros every year.

More importantly, besides logistic and financial consequences, health illiteracy results in worse health outcome parameters, partly because of the fact patients only seek help in a more advanced stage of their disease, and partly because of the impact of not understanding instructions on treatment outcome. Especially the proper use of medication can be a real challenge. Vaginal ovules don’t do very well when swallowed. Injection therapy practiced on an orange, should not be continued on oranges at home. Medication intended for chronic use should not be stopped because the pharmacist only gave pills for two weeks to start with, to make sure there are no side effects. These examples may sound funny, but they do happen.

Mortality rates among illiterates

Sadly, all things combined even lead to higher (complication and) mortality rates in health illiterate patients. In a large Swedish study (S.K. Hussain, 2007) positive association was found with the mortality rates in 13 different cancer types, four of them urological: kidney, bladder, prostate and testicular cancers. Adjusted for all kinds of other socioeconomic factors, compared with women and men completing <9 years of education, university graduates were associated with a significant 40% improved survival for all cancer sites combined. As health illiteracy is more often seen in people with lower education, results like this are of big concern.

What makes it difficult to act on the problem of low health literacy skills is the lack of awareness amongst those who deliver care (“I hardly ever see a patient that can’t read”), but also the tendency amongst patients not to come forward as someone with reading problems. Many of these patients feel ashamed, not in the least because of a society that equals illiteracy with stupidity. They’ve become masters in coming up with excuses like “I forgot my glasses”, “I’ll fill out the form later” or “Oh dear, I forgot to bring the form”. More awareness of the problem and especially a noncondemning attitude amongst care-givers may ease patients to come forward, so extra help can be offered.

Another big step is to adjust the way we hand out – or seek for – information. Instead of forms, leaflets and websites full of text, images, speech and animations should be used. It has been shown that the International Prostate Symptom Score can easily be replaced by one consisting of only a few images, with comparable results. The same goes for voiding diaries with pictograms. Websites full of text could be provided with a ‘read out aloud’-button (also convenient for the visibly impaired). In the Netherlands, the Dutch Urological Association embraced the ‘Aap-Noot-Nier’-project (a urological, humoristic reference to the first three words Dutch people used to learn reading), a project turning leaflets full of text into leaflets with hardly any text at all, but consisting of easy to understand images. The leaflets are made by urologists and low literate people together, as are the corresponding animations.

As all of us who can read perfectly are already shifting from text to images and video’s on our smartphones, tablets and desktops, and the use of spoken animations will not only benefit those who have low heath literate skills. It is known that those who can’t read obtain the same level of information after watching spoken animations as literate people do.

The European Association of Urology is well on its way to invest in new ways of patient education. Challenges include how to make sure these animations reach people that not only have low literacy, but also low digital skills, as well as how to make the animations less fancy and ‘professional’. The more simple the text and the visuals the better the understanding will be. Collaboration with experts in the field and patients therefore is of the utmost importance.

Learn more about this important topic at the dedicated session at the 18th International EAUN Meeting, London.

The session will take place:

Monday, 27 March, 9.45 – 10.15 hrs.,

Room 4 (Level 3).

State-of-the-art 6: Illiteracy and health literacy in patients – Dr. M.R. Van Balken, Arnhem (NL)

Dr. Michael Van Balken, Rijnstate Hospital Dept. of Urology, Arnhem (NL), mvanbalken@rijnstate.nl