6. TRANSRECTAL ULTRASOUND AND BIOPSY PROCEDURE

It is important that the environment is suitably prepared and all the required equipment is available and checked to be in working order before the procedure is commenced. All team members must be aware of their roles and emergency procedures, including the location of the emergency equipment trolley. All staff must have the ability to contact a senior clinician should the need arise.

In order to avoid a mix-up of prostate biopsy samples, it is preferable to:

- Prepare the labels with bar code in advance. These labels should contain name, date of birth and hospital number of the patient who will undergo the prostate biopsies.

- Before the procedure, ask the patient to state their complete name (first and last name) and date of birth to verify the label is correct

- Stick the labels on the histology cassettes.

- When all biopsies are performed, take the labelled histology cassettes with the biopsies tissue to the pathology department immediately.

- As soon as the cassettes arrive at the pathology department, they have to be scanned and saved in the patient record on the computer.

6.1 Room preparation

A spacious clinical room at a comfortable temperature is required, and should be suitably furnished with flooring and equipment that can be decontaminated if there are any spillages of body fluids. The standard equipment required includes:

- examination couch

- curtains/privacy screen

- ultrasound machine

- ultrasound probe

- sharps bin

- linen skip

- clinical waste bin

The following items should be prepared ready in advance:

- procedure checklist

- consent form (signed and dated by patient and clinician performing biopsy)

Ultrasound preparation

- latex-free condom/sheath

- lubricating jelly

Personal protective equipment

- apron

- gloves

Digital rectal examination

- lubricating jelly

Local anaesthesia administration

- local anaesthetic (according to local policy, see recommendations in 6.6.1)

- appropriate size syringe

- dilution needle

- long spinal needle

Biopsy performing equipment

- single use biopsy device

- needle guide

- specimen pots (labelled accordingly with local policies to identify cores)

- pathology requisition form

Post-biopsy

- wipes/gauze

- antibiotics (according to local policy)

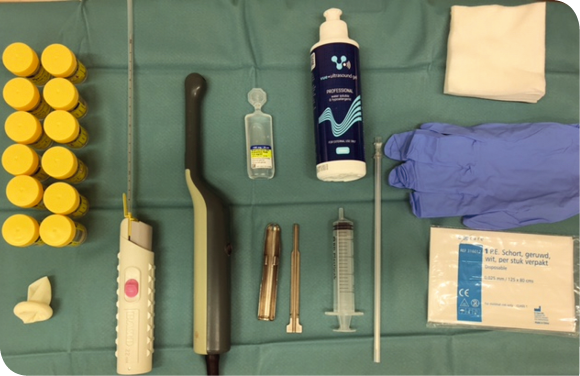

See Figure 8.

Fig. 8 Example of equipment needed for TRUS prostate biopsy

(Courtesy G. De Lauw)

Emergency equipment should be easily accessible in the rare event of a major complication. This should include:

- oxygen

- suction

- cardiac arrest trolley

- defibrillator

- emergency drugs

- anaphylaxis kit

- monitoring equipment

- intravenous fluids

- intubation equipment

6.2 Patient informed consent

Patients should be aware of the potential complications. Before undertaking the procedure the health care professional must seek permission from the patient. This can be either implied or written consent according to local policy. However, for the consent to be valid patients must be competent to make the decision for the investigation to be undertaken. They must have sufficient information to make that decision and not act under duress.

Patients have a fundamental legal and ethical right to determine what happens to their own bodies. Seeking consent is a matter of common courtesy between health care professional and patient. It is not a legal requirement to seek written consent in all countries but it is recognised as good practice, particularly if the procedure comes with significant risks or side effects or the procedure involves regional anaesthesia or sedation.

Informed consent should include [94]

- what the examination involves

- what is its purpose

- what are the risks

- whether the risk is major or minor

- what happens if the examination is not undertaken

However you should familiarise yourself with your local or national consent policy, if there is no policy you might want to consider the implications of your practice as a nurse. [95]

Patients should be made aware of the risk of a false-negative test result and the potential need for repeat biopsy.

The health care professional responsible for carrying out the procedure is ultimately responsible for patient consent for the examination. [60, 61, 62]

| Recommendation | LE | GR |

| • Ensure that the patient understands the potential complications of the procedure, including any risk factors specific to them | 4 | A |

6.3 Transrectal ultrasound

The prostate gland can be visualised with a transrectal probe allowing close-contact scanning. [13] Ultrasound is essential for examining the echotexture and size of the gland and to aid precision biopsy. It is more accurate than DRE in measuring prostate size. [96]

Fig. 9. Ultrasound machine

(Courtesy: BK Ultrasound)

6.3.1 Probe choice and preparation

The ultrasound probe is a dedicated use probe and can vary in frequency between 6 and 9 MHz; the most frequently used being 7.5 MHz. The probe allows visualisation of the prostate in both the transverse and sagittal planes. Probes are end-firing, biplane or both, and there are several designs marketed by different manufacturers. In practice, the design of the probe is not important as full glandular scrutiny is achieved with either design; however, if true anatomical views are required then a biplane probe is essential. [13] The probe is covered preferably with a latex-free condom or probe cover and is decontaminated according to the manufacturer’s recommendations before and after each patient.

6.3.2 Patient positioning

The patient is positioned in the left lateral position ensuring that the knees are bent up towards the chest, or in the lithotomy position. The left lateral position is preferred; particularly with the end-firing probe because imaging of the apex is easier and more comfortable. [13]

6.3.3 Performing a DRE

Immediately before the rectal probe is inserted, DRE should be performed. Particular attention should be paid to the anal tone because a tight sphincter may render the procedure particularly painful. A circumferential examination of the rectum should be performed, followed by examination of the prostate, which includes size, symmetry on both sides, presence of nodules or induration, tenderness and pain in the prostate. Careful attention should also be paid to exclude the presence of anal pathology such as fissures, haemorrhoids and rectal tumours. If a fissure is present it is unlikely that the patient will tolerate introduction of the probe. If a haemorrhoid is present then care must be taken to avoid puncturing it, otherwise there will be profuse bleeding. If a rectal tumour is felt, the procedure should be abandoned and in all circumstances consideration should be given to colorectal referral.

6.4 Ultrasonic appearance

The sonographic appearance is a combination of the gross and zonal anatomy. The peripheral zone has a homogeneous texture (same level of echoes) throughout and is more echogenic (brighter) than the rest of the gland. The rest of the gland has a heterogeneous texture (different levels of echoes) and poor echo. [13] It is not possible to differentiate between the central and transition zones on TRUS. [13] When scanning the gland the seminal vesicles can be seen from the base in the transverse view and near the lateral in the sagittal view.

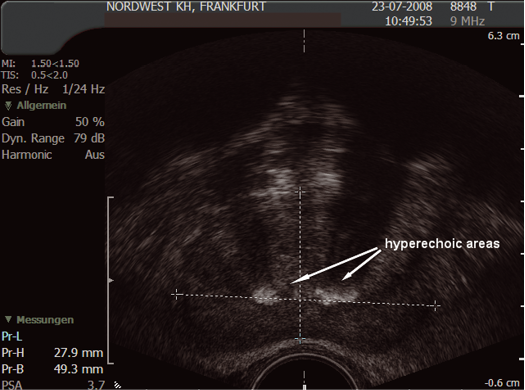

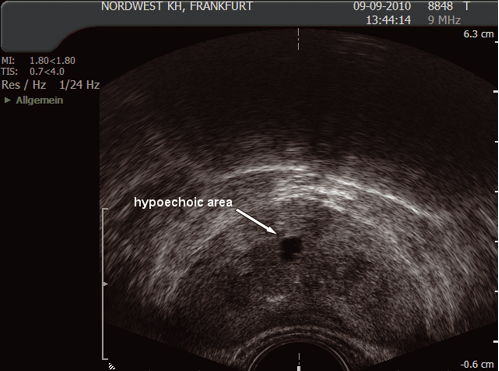

The sonographic appearance of the prostate is not specific but there are three ultrasonic findings that may be described as isoechoic (same echogenicity as surrounding tissue), hyperechoic (brighter) or hypoechoic (darker). (Figs. 10 and 11)

Fig. 10. Hyperechoic areas

(Courtesy: S. Hieronymi)

Fig. 11. Hyperechoic areas

(Courtesy: S. Hieronymi)

Ultrasonic findings:

- isoechoic area could be normal tissue or tumour

- hypoechoic area could be cyst, abscess or tumour

- hyperechoic area could be calcification or tumour

Although these findings are interesting, they should not have any impact on the biopsy procedure or cause additional complications.

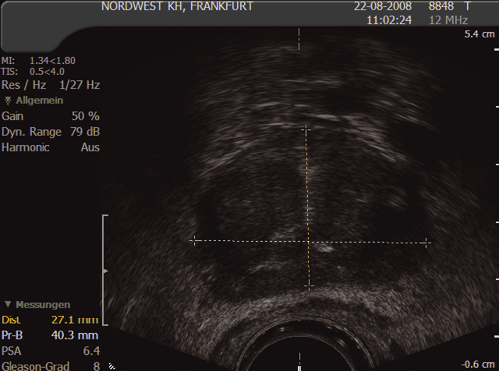

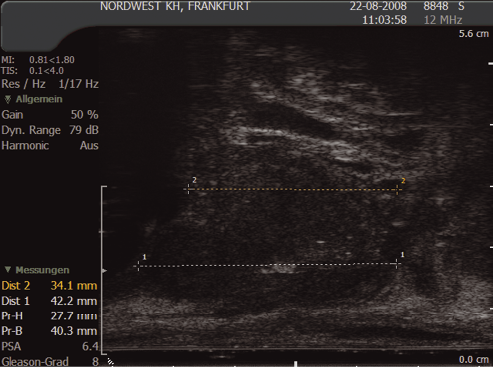

6.5 Prostate measurement

It is routine to measure the prostate volume (in g/ml)), which may be important in offering treatment options. The prostate is measured in three planes:

In the transverse view: anterior to posterior (width) (1) and height (2); and in the longitudinal plane from the bladder neck to the apex (length) (3). This can be calculated using the formula:

Ω/6 × height × width × length (in cm) (Ω/6 may be substituted by 0.51)

Most ultrasound machines will automatically calculate the volume.

Fig. 12. Prostate measurement – transverse view

(Courtesy: S. Hieronymi)

Fig. 13. Prostate measurement – sagittal view

(Courtesy: S. Hieronymi)

6.6 Prostate biopsy

6.6.1 Local anaesthesia

Ultrasound-guided administration of periprostatic nerve block (PPNB) with lidocaine is currently the most reported anaesthetic technique. It is effective in pain control and its effect is immediate, so there is no need to wait to begin the procedure after administering the anaesthetic [97] (LE 1b). To perform PPNB the anaesthetic should be preferentially infiltrated into the junction between the prostate and the seminal vesicles bilaterally [97,98] (LE 1b and 2a, respectively).

The use of intrarectal local anaesthetics alone shows less efficacy in pain control. However, combining the use of intrarectal local anaesthetics with PPNB is a safe technique that provides less sensation of pain during the procedure. [99] (LE 1b)

Intrarectal local anaesthesia can be performed with lidocaine gel or with a mixture of 2.5% lidocaine and 2.5% prilocaine. The administration should take place up to 30 min to 1 h before the biopsy [99,100] (LE 1b).

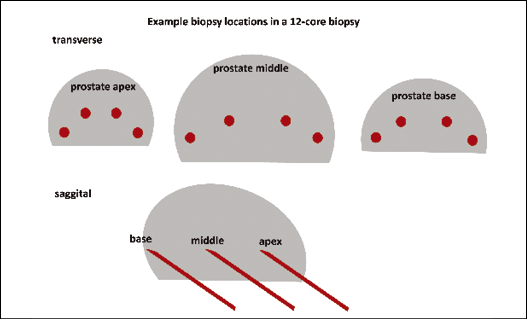

6.6.2 Number and location of prostate cores (PICO 1)

Conventional sextant biopsies were introduced by Hodges et al. in 1989. [101] Later, several studies have shown that this scheme is insufficient for detection of prostate cancer (under-sampling). [102–106] The number of prostate cores to detect prostate cancer has been controversial but concerning initial prostate biopsies, the cancer detection rate is sufficient at 10–12 cores [103,104,107–114]. Additional cores should be obtained from suspect areas by DRE/TRUS. [59] In order to increase the cancer detection rate in a large prostate, additional cores could be obtained, although the results of studies are not consistent concerning the cut-off in prostate volume and the optimal number of prostate biopsies. [102,111,113,115] Randomised studies have shown that a personalised biopsy core scheme according to age, PSA and prostate volume [116] does not increase the cancer detection rate compared to 8–10-core schemes. [109,117] Saturation prostate biopsies are not recommended in initial setting. [108,114,118] An increase in the number of cores does not affect the capacity of biopsy tumour volume to predict final tumour volume after prostatectomy. [119]

At repeat biopsies, an extended core scheme (>12) could be performed in order to detect prostate cancer [110,120], including transition zone biopsies. [110,115]

Random prostate biopsies are still standard for detecting prostate cancer but evidence is accumulating for MRI target biopsies in addition to random biopsies. [38,59]

Location of 12-core scheme biopsies: apex, middle and base of the right lateral (RL), right medial (RM), left medial (LM) and left lateral (LL) parasagittal planes of the prostate.

Fig. 14. Example biopsy locations in a 12-core biopsy

(Courtesy: S. Hieronymi)

6.7 Acute complications and their management

Although prostate biopsy can be achieved in an outpatient setting, most men experience at least one minor complication following the procedure.

Table 8. Complications and their frequencies [121,122]

| Minor | % | Serious | % |

| Visible haematuria | 66.3 | Urosepsis | 0.5 |

| Haematospermia | 38.8 | Rectal bleeding requiring intervention | 0.3 |

| Rectal bleeding | 28.4 | Acute urinary retention | 0.3 |

| Vasovagal symptoms | 7.7 | Transfusion | 0.05 |

| Genitourinary tract infection | 6.1 | Fournier’s gangrene | 0.05 |

| Prostatitis | 1.0 | Myocardial infarction | 0.05 |

| Epididymitis | 0.7 |

Haematuria is the most frequently seen complication following TRUS-guided biopsy. It normally persists for between 3 and 5 days but is self-limiting. The formation of clots and the development of retention can occur and it is wise to ensure that men have successfully voided before leaving the department.

Minor rectal bleeding is common and usually resolves over the first 48 h. Rectal bleeding requiring intervention is rare. In the majority of cases, inserting a Foley catheter into the rectum, inflating the balloon with up to 50 mL, and using traction to compress the bleeding points is sufficient to achieve haemostatic control. At least this allows one to control the bleeding while summoning assistance. Rarely, colonoscopy or endoscopic sclerotherapy may be required.

Vasovagal symptoms such as sweating, nausea, paleness, dizziness, and hypotension are commonly seen. They are more common in the presence of anxiety or hypoglycaemia. However, these symptoms resolve if the patient is left lying flat or in slight Trendelenburg position. Rarely, intravenous fluids may be required.

Although the data are not always clear, it is likely that TRUS-guided prostate biopsy causes worsening of sexual function at least over the short term (3 months). This appears to be more pronounced for men over the age of 60 years and for those subsequently found to have prostate cancer. [123]

6.8 Patient information on discharge

Patients with a urethral catheter, or those with diabetes, should be closely monitored for signs of sepsis. Patients should be advised on rest, fluid intake, frequency of urination, prophylactic antibiotics and follow-up.

There is no definitive data to confirm that antibiotics for long courses (3 days) are superior to short-course treatments (1 day), or that multiple-dose is superior to single-dose treatment.[124]

| Recommendation | LE | GR |

| • Ensure that the patients understand what they must do in case of complications after TRUS biopsy and whom to contact | 4 | A |