6. PRINCIPLES OF MANAGEMENT OF NURSING INTERVENTION

6.1 Patient preparation

Consent

Catheterisation is an invasive procedure that can cause embarrassment and physical and psychological discomfort and have a negative impact on the patient’s self-image. To ensure the patient is fully prepared for catheterisation, it is the responsibility of the health care professional to inform the patient of the reasons and necessity for the procedure, and obtain the patient’s permission. [65] In many areas of medicine, patients are required to sign a consent form that indicates agreement for the practitioner to undertake a procedure. It also implies an understanding of the event and the associated potential complications/problems. At present, it is not common practice within Europe for patients to provide written consent for catheterisation; it is however a necessity that verbal consent and agreement is reached and the relevant information is recorded in the patient’s medical and/or nursing notes. [66]

Information and support

Explaining the procedure and providing the reason for catheterisation to the patient will help reduce patient anxiety and embarrassment and help the patient to report any problems that may occur while the catheter is in situ. [67] Relaxing the patient by offering reassurance and support will help smoother insertion of the catheter and avoid unnecessary discomfort and the potential for urethral trauma during insertion. [68, 69]

Preparing the procedure

Even if catheterisation is a prescription by a medical doctor, health care professionals should take a brief medical history, especially about urological conditions, before the procedure.

Catheterisation is a sterile procedure to prevent pathogenic bacteria from entering the urinary tract. It is imperative that health care professionals have a good understanding of the principles of the aseptic procedure as this will help to reduce the risk of UTI. [70]

Lubricating gel

Catheterisation can be painful in men and women. The use of anaesthetic lubricating gels is well known for male catheterisation. An appropriate sterile single-use syringe with lubricant should be used before catheter insertion of a non-lubricated catheter to minimise urethral trauma, discomfort and infection. [12] However, it is essential to ask patients if they have any sensitivity to lignocaine/lidocaine, chlorhexidine or latex before commencing the procedure. There have been reports of anaphylaxis attributed to the chlorhexidine component in lubricating gel [71], and in some institutions chlorhexidine is now banned because of this. Ten to fifteen millilitres of the gel is instilled directly into the urethra until this volume reaches the sphincter/bladder neck region. [72-76] Blandy [77] and Colley [78] recommend a 3–5-minute gap before starting catheterisation after instilling the gel, but it is important to follow the manufacturer’s guidance. A maximised anaesthetic effect will help the patient to relax and insertion of the catheter should be easier. [79]

If the lubricant contains lignocaine/lidocaine or chlorhexidine, care should be taken if the patient has an open wound, or severe damaged mucous membranes and/or infections in the regions where the lubricant will be used. In patients with severe disorders of the impulse conduction system or epilepsy, as well as women in the first 3 months of pregnancy, or breastfeeding (Package instruction leaflets Instillagel® and Xylocaine®), urologists should seek permission to use a lignocaine/lidocaine-containing lubricant. [72-76]

Rare but serious allergic reactions (anaphylaxis) have been reported with widely used skin antiseptic products and lubricants containing chlorhexidine gluconate. These reactions can occur within a few minutes of exposure. Symptoms include wheezing or difficulty breathing; swelling of the face; hives that can quickly progress to more serious symptoms; severe rash; or shock, which is a life-threatening condition that occurs when the body is not getting enough blood flow. Lubricants which contain chlorhexidine have been reported to trigger anaphylaxis in a small number of patients during catheter insertion and consequently a careful history is required to screen for sensitivities. [80]

| Recommendations | LE | GR |

| Obtain verbal consent from patients for indwelling catheterisation before starting the procedure | 4 | C |

| Ask patients if they have any sensitivity to chlorhexidine [71], lignocaine/lidocaine or latex before commencing the procedure | 4 | A |

| Educate and train health care professionals to have a good understanding of the principles of the aseptic procedure as this will help reduce the risk of UTI [24, 70] | 1b | B |

6.2 Urethral catheter – female and male insertion procedure

For practical guidelines on how to insert a male or female urethral catheter see Appendices B and C.

The recommendations below are for catheterisation in men; recommendations with * are also relevant for women.

| Recommendations | LE | GR |

| If resistance is felt at the external sphincter, increase the traction on the penis slightly and apply steady, gentle pressure on the catheter. Ask the patient to strain gently as if passing urine | 4 | C |

| In case of inability to negotiate the catheter past the U-shaped bulbar urethra use a curved tip (Tiemann) catheter, or hold the penis in an upright position to straighten out the curves, or ask the patient to cough | 4 | C |

| Special catheters, such as Tiemann, need a special technique and should be attempted by those with experience and training [69, 81-83] | 4 | C |

| During insertion, a Tiemann tip must point upward in the 12 o’clock position to facilitate passage around the prostate gland [44] | 4 | C |

| When inserting the urethral catheter use a sterile single-use packet of lubricant jelly [24] * | 4 | C |

| Routine use of antiseptic lubricants for inserting the catheter is not necessary [24] * | 4 | C |

| A small lumen catheter can buckle/kink in the urethra; in some instance a slightly larger Charrière size might help [83] * | 4 | C |

| Further research is needed for using the non-touch technique for indwelling urethral catheterisation * | Unresolved issue | |

| Connect the catheter to the sterile bag and then insert the catheter using aseptic technique, because an aseptic closed drainage system minimises the risk of CAUTI *[18] | 4 | A |

* Recommendation also relevant for females

6.3 Suprapubic catheter insertion procedure

A distinction should be made between initial insertion and changing of the catheter. For initial insertion sterile technique is used and the procedure is normally carried out by a urologist.

Advanced Practice Nurses can do initial insertion of a suprapubic catheter if this falls within their scope of practice. An experienced urology nurse should do the first suprapubic catheter change. Thereafter a competent health care professional can do the insertion.

If the patient does not have a readily palpable bladder, then the bladder should be filled with at least 300 ml of 0.9% saline prior to insertion of a suprapubic catheter. A bedside ultrasound should be used in high-risk patients (previous abdominal surgeries and colostomy, obese, hernias or in those with previous indwelling catheters and small capacity bladder such as some neurogenic patients, as an adjunct to suprapubic catheter insertion. The purpose is to ensure that the needle used to make the suprapubic catheter tract can be visualised entering the bladder at an appropriate point on the anterior bladder wall.

In patients with a history of lower abdominal surgery or in whom the bladder cannot be distended, an open procedure may have to be performed for insertion of the suprapubic catheter. [84] (LE 3)

For practical guidelines on how to insert a suprapubic balloon catheter see Appendix D.

| Recommendation | LE | GR |

| Further research is needed for using the non-touch technique for suprapubic catheters | Unresolved issue | |

6.4 Difficulties that may occur during insertion

Difficulty in catheterising the patient can be caused by a variety of reasons. Medical advice and support should be sought if problems during or after the insertion occur. Complications associated with insertion of transurethral or suprapubic catheters include UTI, trauma and inflammatory reactions, and possibly carcinoma of the bladder [85], and for transurethral catheterisation, also via falsa (accidental passage made when inserting the catheter) and urethral strictures. These can result in one or more of the following symptoms occurring: pain, bypassing of urine, blockage, catheter expulsion and bleeding.

Urethral trauma can be caused by any catheter size or by forced insertion of the catheter or incorrect position of the catheter tip. Urethral trauma should be minimised by the use of adequate lubricant, the smallest possible catheter size, or a special catheter for difficult catheterisation and the correct insertion technique. [14] (LE: 1b) [86-88]

6.5 Catheter care/maintenance

6.5.1a Meatal cleansing before insertion

In a meta-analysis about meatal cleansing before insertion and for catheter care, there was no significant difference in CAUTI rates for cleansing with water/water and soap versus use of antiseptic solutions. [89]

In another meta-analysis, Huang et al. [90] compared cleansing with water versus antiseptic before catheter insertion. They found no significant difference between water versus povidone iodine and water versus chlorhexidine gluconate. They concluded that use of water for cleansing the meatus was not associated with increased risk of UTIs. [90]

One cross-sectional, stepped-wedge, open-label, randomised controlled trial (RCT Fasugba, 2019) found, after adjusting for age, sex, and clustering by hospital, that the use of chlorhexidine was associated with a significantly reduced risk of catheter-associated asymptomatic bacteriuria and CAUTI. [91] However, a new systematic review that included this study found no significant difference between cleansing with water versus chlorhexidine. [92]

6.5.1b Meatal cleansing when catheter is in place

Routine daily personal hygiene is all that is needed to maintain meatal hygiene. [24, 89, 92]

Trials of various cleansing agents, e.g. chlorhexidine and saline, have failed to demonstrate a reduction in bacterial growth rate [93], meaning soap and water is sufficient to achieve effective meatal cleansing. [13, 69, 94] However, attention must be given to educating non-circumcised patients to clean underneath their foreskin daily to remove smegma, as this may increase the patient’s risk of developing a UTI, in addition to causing trauma and ulceration to the meatus and glans penis. [95, 96]

There is no evidence that routine application of antimicrobial preparations around the meatus will prevent infections. [13, 69, 97]

6.5.2 Care of urethral catheters

Whichever bag is chosen, extensive measures should also be taken to maintain unobstructed flow. [24] To prevent obstruction, the catheter and collecting tube should be kept free from kinking and the collecting bag has to be kept below the level of the bladder at all times (to allow urine to drain by gravity) and must never be rested on the floor. [24]

When emptying the collecting bag, regularly use a separate, clean collecting container for each patient; avoid splashing, and prevent contact of the drainage spigot with the non-sterile collecting container. [24]

| Recommendations | LE | GR |

| Perform hand hygiene immediately before and after any manipulation of the catheter and system. Wear disposable gloves when handling the system | 1b | B |

| Maintain unobstructed urine flow [24] | 1b | B |

| Keep the catheter and collecting tube free from kinking [24] | 1b | B |

| Keep the collecting bag below the level of the bladder at all times. Do not rest the bag on the floor [24] | 1b | B |

| Empty the collecting bag regularly using a separate container for each patient; avoid splashing, and prevent contact of the drainage spigot with the non-sterile collecting container [24] | 1b | B |

6.5.3 Care of the suprapubic catheter site

| Recommendations | LE | GR |

| Always ensure good hand hygiene is performed prior to any intervention [97] and use protective equipment; e.g., gloves | 1b | B |

| Suprapubic catheter site should be cleaned daily with soap and water. Excess cleansing is not required [13, 69] and may increase the risk of infection | 1b | B |

| Observe the cystostomy site for signs of infection and over-granulation | 4 | C |

| Antimicrobial agents should not routinely, or as prophylactic treatment be applied to the cystostomy site to prevent infection [97] | 1b | A |

| Dressings are best avoided. If a dressing is used to contain a discharge this should be undertaken with strict aseptic technique to protect against infection | 4 | C |

| Wherever possible, patients should be encouraged to change their own dressings [98] | 4 | C |

6.5.3.1 Observation and management of catheter drainage

The observations relate to the indication for catheterisation. Postoperative catheterisation is often performed to monitor urine output. The monitoring of urine output is vital to ensure that the bladder continues to empty and that excessive diuresis does not occur. [99] In home settings, observations relate to common complications of long-term catheters such as blockage and UTIs.

For common problems with indwelling catheter equipment, see Appendix E.

For observation of urinary drainage, see Appendix F.

In case of problems with drainage due to blockage or encrustation, Mitchell, 2008 [100] developed an evidence-based long-term urinary catheter management flow chart. She reviewed the literature for evidence. As a result, for example, in this chart there is no recommendation about catheter maintenance solutions, because there is no evidence for this. It is a tool to be discussed with the patient and the clinical team on an individual patient basis. In case of blockage, the literature advises to look back over at least the last 3 catheter changes (the catheter change record can be used for this).

Decision flow chart on catheter drainage (adapted from Mitchell 2008) [100], see Appendix R

Indwelling catheters with open-drainage systems result in bacteriuria in almost all cases within 3–4 days. [14, 55] By using closed urinary drainage systems bacteriuria cannot be prevented, but it can be delayed. Almost all patients will develop bacteriuria within ~ 4 weeks. [14] Breaking a closed drainage system to obtain urine samples increases the risk of CAUTI. [101] If the closed drainage system is broken, aseptic technique should be used to reconnect the system. [102]

| Recommendations | LE | GR |

| Keep the catheter and collecting tube free from kinking and maintain unobstructed urine flow [24] | 1b | B |

| Keep the collecting bag below the level of the bladder at all times | 1b | B |

| When emptying the collecting bag regularly, use a separate, clean collecting container for each patient; avoid splashing, and prevent contact of the drainage spigot with the non-sterile collecting container | 1b | B |

| Unnecessary disconnection of a sealed (pre-connected) drainage system should be avoided but if it occurs, the catheter and collecting system have to be replaced using aseptic technique and sterile equipment | 1b | B |

| Catheter and drainage tubes should never be disconnected unless for good clinical reason | 2b | B |

| Disinfect the catheter/collecting tube junction before connecting | 4 | C |

| Use of a urometer that allows accurate measurement is recommended in intensive care patients [103] | 2b | B |

| Complex urinary drainage systems are not necessary for routine use | 2b | B |

| Catheters and drainage bags should be changed based on clinical indications such as infection, obstruction, or when the closed system is compromised and not routinely [24] | 1b | B |

6.5.3.2 Fixation and stabilisation of the urethral catheter

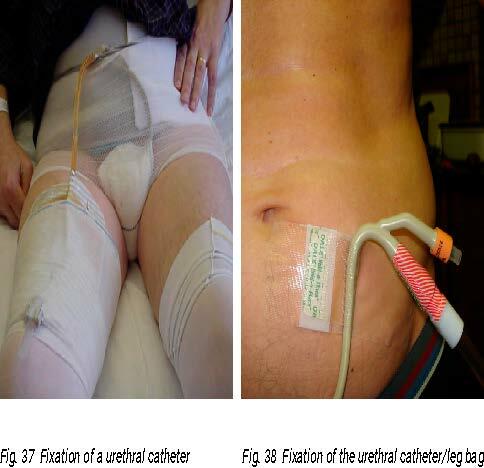

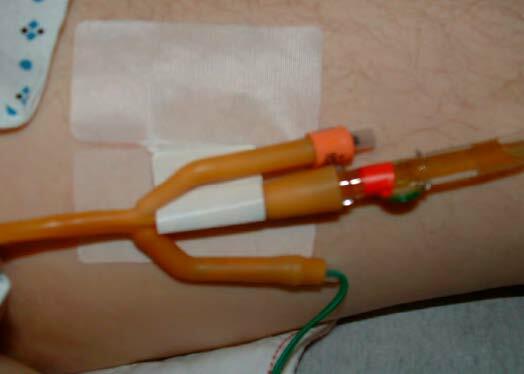

Stabilisation of urethral catheters can reduce adverse events such as dislodgment, tissue trauma (necrosis), inflammation and UTI. [103-105] The use of a securement device also reduces physical and psychological trauma by decreasing the need for re-insertion [24, 106] and can give patients more comfort and confidence. [107]

Securement devices should place no tension on the urethral or abdominal tissue. [107, 108] If the catheter bag becomes too heavy with urine, and it is not supported properly, the bag can pull on the catheter. [24, 106]

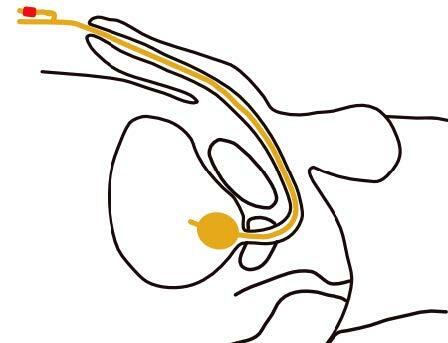

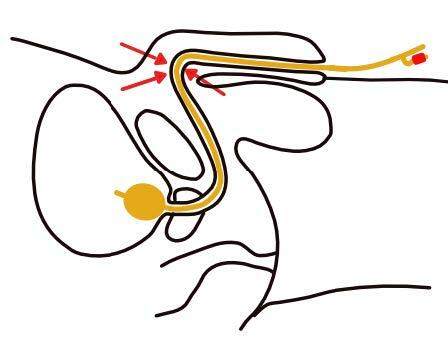

To avoid necrosis at the external urethral meatus continuing down the ventral surface of the penile shaft to the penoscrotal junction caused by prolonged catheter pressure, or cleavage of the urethra or penis, although rare, it is recommended to secure the urinary urethral catheter to the abdomen. [103] The catheter has to be positioned in a soft curve towards the femur (Fig. 34) and can be fixed with a securing device, tape, Velcro™ and a pocket for the bag (Figs. 37, 38, 39).

Although the references are only for urethral catheterisation, the same principles of stabilisation apply to suprapubic catheters. [109]

Fig. 34 Correct fixation of the indwelling urethral catheter to the abdomen in males, especially spinal cord injured patients

(Courtesy of V. Geng)

Fig. 35 Wrong fixation of the indwelling urethral catheter in males

(Courtesy of V. Geng)

Fig. 36 Iatrogenic hypospadias developed after indwelling urethral catheterization

(Courtesy of Wiley.com)

Left: Fig. 37 Fixation of a urethral catheter

(Photo courtesy of C. Vandewinkel)

Fig. 38 Fixation of the urethral catheter/leg bag

(Photo courtesy of C. Vandewinkel)

Fig. 39 Fixation of the catheter with a securement device

(Photo courtesy of D.K. Newman)

| Recommendations | LE | GR |

| Secure and stabilise the catheter after insertion to prevent movement and urethral traction [24] | 1b | B |

| In men, secure the urinary catheter to the abdomen and in women, to the leg | 4 | C |

6.5.3.3 Clamping or not

Bladder dysfunction and postoperative voiding impairment have been documented following catheterisation and these can lead to UTI. Intermittent clamping of the indwelling urethral catheter draining tube prior to withdrawal has been suggested on the basis that this simulates normal filling and emptying of the bladder. While clamping catheters might minimise postoperative neurogenic urinary dysfunction, it could also result in bladder infection or distension. A Cochrane review compared clamping the indwelling urethral catheter prior to removal with free drainage in patients with a short term indwelling catheter and found that there may be little to no difference between clamping and free drainage on the risk of needing the catheter to be reinserted. There is uncertainty if there is any difference in the risk of UTIs or painful urination. [110] Another review included adults who required an indwelling catheter concluded that clamping urinary catheters increases the incidence of UTI and lengthen the hours to first void in patients with indwelling urinary catheters for ≤ 7 days compared with the free drainage. The effect of clamping training on the duration of indwelling urinary catheters for > 7 days is uncertain. Therefore, bladder training with clamping before catheter removal is not recommended as a routine method [111]

The pooled results of the meta-analysis showed that the clamping group had a significantly higher risk of urinary tract infections (p < 0.00001) and a longer hour to first void (p = 0.0004) compared with the free drainage group in catheter use duration ≤ 7 days. [111]

| Recommendation | LE | GR |

| It is uncertain whether there is a benefit in clamping before urinary catheter removal. [111-113] | 1a | A |

6.6 Changes in urine due to food and medication

The presence of an appliance for collecting urine increases patients’ awareness of odour and colour changes affecting the urine caused by some drugs and food products (Appendix G). Patients and carers should be told that these changes are not harmful and do not necessarily occur in all patients. Normal urine is clear, straw-coloured with almost no odour. A pungent odour, due to the production of ammonia, is typical of most bacterial urinary tract infection, whereas there is often a sweet or fruity odour with ketones in the urine. Some rare conditions confer a characteristic odour to the urine. [109]

See table Possible colour and odour changes in urine due to food or medication, Appendix G.

Purple urine bag syndrome

Purple urine bag syndrome (PUBS) is a rare condition and is characterised by purple discolouration of the urine bag, appliances and catheter tubing. The urine itself may be dark in colour and not necessarily purple. The condition appears to have a significantly higher incidence in women and chronically debilitated patients with long-term indwelling urinary catheters. [114-116] The major risk factors for PUBS are female gender, severe constipation, chronic indwelling urinary catheterisation and increased tryptophan dietary content. [102,103] The purple colour is caused by bacterial metabolism of tryptophan to indole and later converted to indican in the liver. Indican passes through the kidney giving urine a purple/blue/grey colour. [116, 117]

Although studies have shown certain factors like constipation and UTI may be present, these factors are not found consistently. [115, 118] PUBS is generally found to be harmless, but there have been case reports describing PUBS progressing to Fournier’s gangrene. [119] The discolouration of urine and the urine bag can be distressing for patients, family and health care workers; therefore, they should be educated to manage this syndrome. [120] The incidence is reduced by avoiding constipation and proper care of the urinary catheter. [115, 118]

| Recommendation | LE | GR |

| If urine changes odour or colour, check what could be the reason for this change | 4 | C |

6.7 Constipation

Constipation may cause pressure on the drainage lumen that prevents the catheter from draining adequately, which can cause ureteric reflux and back pressure on the kidneys. [121-123] Chronic constipation may also cause leaking of urine and bladder spasms. [124] Maintaining regular bowel function with a high-fibre and high-fluid intake helps prevent constipation. [124, 125]

| Recommendations | LE | GR |

| Bowel assessment should be made routinely in case of catheter problems | 4 | C |

| Educate the patient regarding the link between constipation and bypassing urine and constipation and UTI [121-125] | 4 | C |

6.8 Urethral and suprapubic catheter change

- There are two techniques to change a urethral or suprapubic catheter. The classic method is with the use of sterile gloves. The second method is the “non-touch technique” without sterile gloves. Instead, the sterile package of the catheter is used to touch the catheter. There is still no evidence for the non-touch technique and attention should be on reducing the risk of cross-contamination.

- Catheter change depends on the material of the catheter. A latex catheter is changed after 2 weeks to a hydrogel or silicone catheter and a silicone catheter is changed after 12 weeks unless any catheter-related problems such as catheter blockage and catheter damage are identified.

- For both urethral and suprapubic the frequency of catheter change is instructed by a medical doctor.

- Long-term catheters can be changed on an individual basis to try to avoid problems. However, the catheter must be changed within the timeframe recommended in the manufacturer’s instructions, which may be up to a maximum of 12 weeks.

- Check the catheter for encrustation after removal. Use a catheter diary to recognise when the catheter gets encrusted and plan changing the catheter before encrustation happens.

- If the catheter change is uneventful, a classic catheter with open eyes at the side and a closed eye at the end is preferred. In case of severe problems with changing the catheter, a changing set (with guide wire) and a catheter with an open end should be used.

Antibiotics are not routinely given prior to catheter change but may be prescribed for patients deemed at risk of infection at the physician’s discretion.

Following initial insertion of a suprapubic catheter, the tract will take between 10 days and 4 weeks to become established, after which time the catheter can be changed safely.

Comply with local protocols and procedures with regard to change of catheter (male and female).

For Preparation and procedure for changing suprapubic catheter, see Appendix H.

The procedure for changing a urethral catheter can be found in Appendix J and

Appendix B and C where the insertion procedure is described.

6.9 Removal of urethral and suprapubic catheters

Nurses must monitor the need for a catheter carefully.

If removal is considered, it should be discussed with the medical team. Catheter removal should be performed as instructed by a doctor.

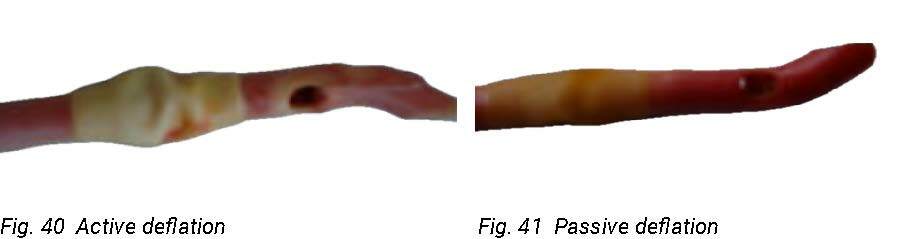

In an in vitro study, the complication of balloon cuffing was observed and passive deflation was the best way to empty the balloon. [126] This is done by allowing the catheter balloon to passively dispel the water. The plunger will move on its own as the syringe fills with water. Do not pull back on the plunger.

Left: Fig. 40 Active deflation

(Photo courtesy of C. Vandewinkel)

Right: Fig. 41 Passive deflation

(Photo courtesy of C. Vandewinkel)

Pain is frequently encountered during removal of urethral and suprapubic catheters and is often a consequence of ridge formation on the catheter balloon. This can be minimised by allowing passive deflation of the balloon rather than applying active suction to the deflating channel. [127]

In a RCT, Mills et al. compared catheter removal with active versus passive void trial. Active void trial (AVT) means that the bladder was filled with saline before removal. Passive void trial means that nothing was done before removing the catheter. The AVT group showed a 3–6-hour reduction in time to void and a 63% reduction in UTI. They concluded that the data suggest that AVT should be considered as a recommended technique. [112]

Du et al (2013) found no significant difference in bladder filling prior to void trial in a small prospective multicentre RCT regarding the time to discharge. [113]

When the catheter has been removed, and advice on lifestyle has been given (e.g., drinking), make sure that the patient understands that they can contact a health care professional at any time if or when problems occur.

The available evidence (in the Cochrane review Ellahi 2021) suggests that the removal of short-term indwelling urethral catheters late at night, in comparison to early in the morning, may reduce the risk of requiring recatheterisation and the risk of dysuria. [110]

The same evidence was uncertain about the effect on the risk of symptomatic CAUTI. [110]

Some evidence revealed that early removal of indwelling urinary catheters after pelvic organ prolapse surgery was associated with a reduced incidence of UTI (RR 0.46, 95% CI 0.24 to 0.9). Compared with catheter removal later than 2 days after surgery, catheter removal within 2 days post-operatively significantly reduced the incidence of UTI. [128]

See Appendix I Removal of an indwelling urethral catheter - protocol, Appendix J Removal of the urethral catheter – procedure and Appendix K Removal of suprapubic catheter – procedure

| Recommendations | LE | GR |

| Minimise pain by allowing passive deflation of the balloon rather than applying active suction to the deflating channel [127] | 3 | B |

| Based on 2 RCTs, it is uncertain whether there is a benefit in clamping before urinary catheter removal. [112, 113] | 1b | C |

| Remove the catheter late at night in patients with short-term catheters [110] | 1a | A |

| More studies are needed regarding the use of active void trial versus doing nothing before catheter removal in patients with a suprapubic catheter [112, 113] | Unresolved issue | |

6.10 Potential problems during and following catheter removal

There are several problems that might arise during removal of a urethral catheter and it is vital that health care professionals are aware of the actions required to overcome them.

Problems and management are listed in:

Appendix L Troubleshooting for indwelling catheters (problem management)

Appendix M Potential problems during catheter removal

Appendix N Potential problems following catheter removal