8. PRINCIPLES OF MANAGEMENT OF NURSING INTERVENTION

Before starting with intermittent catheterisation (IC), some general aspects should be considered:

The decision to start IC is prescribed by a medical doctor or nurse specialist in accordance with local policy. Optimal conditions need to be available, including a well-educated nurse, suitable material, comfortable place, and hygienic toilet with appropriate space. The procedure should be performed either with an aseptic, non-touch or clean technique depending on the setting (hospital, rehabilitation centre, or home) and patient. The patient’s privacy is paramount in all locations. [111, 112]

| Recommendations | LE | GR |

| Observe local policy before starting catheterisation | 4 | C |

| Assess the patients and their individual circumstances for IC before choosing type of catheter, tip and aids | 4 | C |

| Be aware that the patient’s privacy is paramount in all locations [111, 112] | 4 | C |

GR, grade of recommendation; LE, level of evidence.

8.1 Frequency of catheterisation

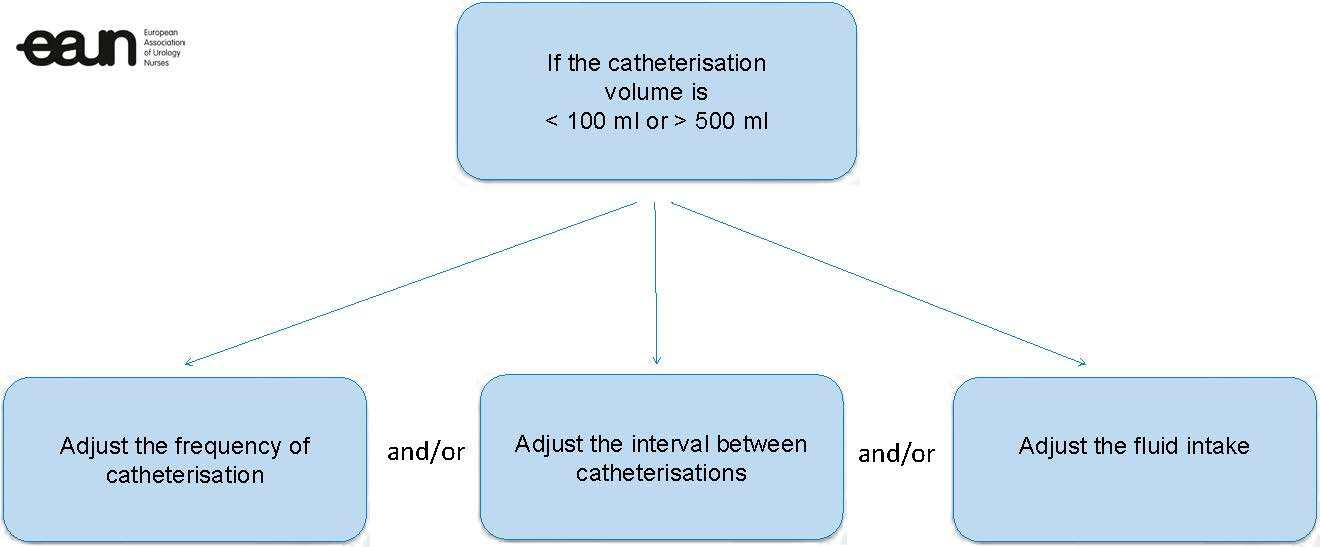

Individualised care plans help identify appropriate catheterisation frequency, based on discussion of voiding dysfunction and impact on quality of life (QoL), voiding diary, functional bladder capacity, and ultrasound bladder scans for residual urine. The number of catheterisations per day varies. In adults, a general rule is catheterising frequently enough to avoid a bladder volume > 500 ml, but guidance is also provided by urodynamic findings such as bladder volume, detrusor pressures on filling, presence of reflux, and renal function [24] (see Diagram 4). A prospective cohort study (n=100) found that patients adherent to the prescribed frequency of catheterisation had less risk of infection than those who were not. [51] Increase the IC frequency if the patient still has the urge to urinate, or has motor restlessness or spasticity.

If the patient is unable to pass urine independently, they will usually require IC 4–6 times daily to ensure the bladder volume remains below 500 ml. Excessive fluid intake increases the risk of over-distension of the bladder and overflow incontinence. [113] Possible leg oedema is eliminated in lying position and the bladder will fill within the first few hours of lying down. Thus, patients should be advised to perform IC shortly before sleep to prevent sleep disturbance and bladder over-distention.

Diagram 4. Options when adaptation of the catheterisation pattern is needed

| Recommendations | LE | GR |

| Assess the frequency of catheterisation if the urine output is > 500 ml or < 100 ml per catheterisation | 4 | A |

| Review the patient’s medication list influencing bladder function (such as anticholinergic medication and ß3 agonists) | 4 | A |

| Perform IC shortly before sleep to prevent sleep disturbance and bladder over-distention | 4 | C |

8.2 Residual urine volume

In the early days of establishing IC, observation and management of bladder emptying and residual volume (including retention) are important to measure the urine volume drained to determine the frequency of IC. [63] Completing a voiding diary (Appendix I) can be helpful to keep a record of the fluid intake, how much urine is voided independently (if any), frequency of catheterisation, and residual volume. The diary can then be used by the health professional, in consultation with the patient and caregiver, to decide whether amendment to the frequency of IC is necessary.

A voiding diary can be found in:

Appendix I: Voiding diary for intermittent catheterisation patients

8.3 Patient and caregiver assessment

While IC is considered the gold standard for assisted bladder drainage [27, 114], it should only be considered and undertaken once the patient has been assessed and is deemed eligible. Patients should be able to perform the procedure correctly and consistently, or designate someone to perform the procedure on their behalf. It is important to manage the patient’s expectations from the beginning. [115] The greater the support of the healthcare team for the multidimensional aspects of patients’ lives, the better treatment adherence will be. [116]

Patients and/or caregivers need to be assessed regarding their:

- ability to understand the information

- knowledge of diagnosis and understanding the need for catheterisation

- knowledge about the urinary tract [117]

- general health status

- ability to perform the skill

- adherence

- need for psychological support

- motivation/emotional readiness

- availability to perform the procedure [111, 118]

Ability to understand the information

For some patients the procedure is complex, especially at the start of the learning process. They have difficulty memorising the procedure or lack organisational skills (e.g., correct sequence of the procedure, organising catheter materials). [119]

Two small studies on adherence to short- and long-term IC found that general determinants for initial mastery and short-term adherence relate to knowledge, complexity of the procedure, misconceptions, and timing of the educational session. These determinants illustrate how IC is not as simple as is often assumed. Obtaining the knowledge required and mastering the necessary skills are a real challenge to patients.

The expert opinion of the Working Group is that, for patients with low cognitive function, it is important that a caregiver or healthcare provider accompanies the patient during a training session. By asking the patient to repeat the training skills, one can check whether the explanation has been understood. [120] Sometimes more than one training session is needed and shorter follow-up can be helpful. Also, contacting a community nurse who can take care of these patients at home can be a solution. Occasionally, an alarm watch (or mobile phone) can be helpful when patients have difficulty in remembering to perform IC.

In a study of multiple sclerosis (MS) patients with different cognitive levels and bladder emptying problems, 87% were able to learn clean intermittent self-catheterisation (CISC) in spite of cognitive function. The number of training sessions required was 2–6 for men and 2–11 for women. Patients did not use written materials or other devices in this study and there was no description of which catheters were used. [119]

Determining the self-confidence of the individual regarding IC application and supporting it when necessary is a prerequisite for successful implementation. [121]

A variety of educational media should be used in suitable patients to facilitate patient/carer learning. [122] Online content allows repeated and remote access to suit patients’ needs. [121]

General health status

Before starting information and instruction for IC it is necessary to assess the general health status to determine if there are any barriers to performing IC.

Knowledge about the urinary tract

Patients need to have a basic knowledge of the urinary tract. One study showed that, in older women, mastery of IC is complicated by limited knowledge of their own bodies. [58]

In caregivers, long-term adherence to catheterisation can be influenced by fear of damaging the urinary tract. [123] Therefore, teaching strategies for clean intermittent catheterisation (CIC) should ensure that caregivers are familiar with the basic anatomy and function of the lower urinary tract. [117]

Ability to perform the skill

The outcome of IC training depends on several patient skills (motor, cognitive, psychological and behavioural) and environmental factors. Lack of motor skills (how to sit or stand in patients with neurological problems, such as tetraplegia), fine motor skills (dexterity, limited hand function), and sensory skills, as well as poor vision, can cause difficulties when learning or performing CISC. [116, 124] Impaired manual dexterity (e.g., tetraplegia) or catheter type used for IC does not seem to affect the stricture occurrence rate. [80]

In particular, women can experience difficulties in finding the urethra and need to use a mirror prior to inserting the catheter. [58, 125] Special devices have been developed, and when the patient is motivated, it is usually possible to succeed. [126]

Examples of special devices can be found in: Appendix H: Help (supporting) devices

If the patient does not have the ability to perform ISC appropriately, an educated and adapted person (such as their spouse, caregiver or guardian) should be identified and trained to undertake the procedure. [116]

Convenience and speed of use are important because many people have to fit IC into their busy lives. [127] For patients to continue to use IC successfully as part of their daily routine, the procedure must be made as easy as possible. Some patients find learning the technique difficult and may discontinue because they find the task too burdensome.

A group of 160 females undergoing pelvic reconstructive surgery that needed postoperative ISC were instructed to perform the procedure at home, which included a demonstration video about ISC. In addition, study personnel contacted participants within 72 h of surgery to assess their ease and ability to perform ISC after surgery. After two weeks they answered a questionnaire and 85% of participants felt that the ISC instructions were “very easy to understand”; 10.6% felt they were somewhat easy to understand; and the remaining 4.2% found that the instructions were somewhat or very confusing. Likewise, 82.0% felt that performing ISC at home met or exceeded their expectations. [128]

Adherence (compliance)

IC adherence is key to maintenance of health and renal function and to manage lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). Adherence can be demanding for an individual [115, 129] and educational, emotional and psychological support and regular reviews are essential. [130, 131] A small study found that the median time required to self-catheterise with the necessary material ready (specific duration) was 2.23 min (range 47 s to 11.5 min). The time spent on catheterisation did not influence adherence. [132]

There are many factors that influence adherence, such as:

- knowledge of the procedure and the body

- complexity of the procedure

- physical impairments

- psychological factors

- misconceptions

- fears of negative effects of IC

- fear of lack of self-efficacy

- embarrassment

- resistance to the sickness role - availability of materials

- timing of the educational session

[58, 111]

Any of these factors can result in avoiding activities or non-adherence to prescribed IC. Healthcare professionals’ communication skills and attitudes are instrumental in promoting confidence and can help patients to overcome their (initial) resistance [111, 120] and increase adherence. [133]

More information on how to help patients adapt to the new lifestyle can be found in Sections 8.4 Patient and caregiver information and 8.5 Ongoing support and follow-up.

Motivation/emotional readiness

Lack of patient motivation is the most common reason for failure. [134] Nurses need to be aware that patients can experience shock and embarrassment, and investigating the needs and desires of the patients is of great importance. [135] Recognising and responding to the patients’ emotional reaction to learning to self-catheterise can improve the patients’ motivation, compliance, self-esteem and psychological wellbeing. Investigating the motivation of the patient is also important for successful assessment. [58]

The desire to maintain independence is a motivating factor in patients’ acceptance and adherence to performing CIC. [136]

Fear of negative effects of IC and lack of self-efficacy persist over time and can have a negative impact on long-term adherence. Patients perceive the combination of IC and having an active social life as difficult and seem to refrain from activities or become non-adherent to prescribed IC frequency. Some older patients tend to avoid situations that compromise adherence, and some younger patients struggle with the difficult combination of IC and their self-image, independence, the routines they wish to maintain, and their intimate relationships. Young patients often have resistance to a sickness role. [58]

Need for psychological support

The psychological implications for people who need to learn and perform IC often pose the biggest challenge to this treatment. Therefore, for nurses to provide an effective service and to train and support patients, it is important to explore and address patients’ psychological, emotional and practical needs, including correct communication, information giving, and attitudes. [111] If patients experience ongoing problems, they should be referred to a sexologist or psychologist.

Performing IC outside the patient’s own home

Some patients, especially older people, find it difficult to perform IC outside their own house, because they are afraid of poor hygienic sanitary conditions, and the risk of urinary tract infection (UTI) because of this. [58]

Many external barriers to performing IC are specific to the design of public restrooms, poor access for people in a wheelchair and poor hygiene. [137] This makes it difficult to perform IC using the correct technique and maintain hygiene. Patients should be educated in how to manage these barriers to maintain social activities outside their own home.

Patients and caregivers should be encouraged to express any psychological issues about IC because of the intimacy of performing such a procedure. [135, 138, 139] Patients and caregivers should be aware of contingency plans of who will perform IC if caregivers are unable due to illness or holidays, for example.

Even though IC is the gold standard in bladder management, it might be preferable to use an indwelling catheter for a short period, for instance, during a flight where there is a minimum of sanitary circumstances. [140]

A medical travel document could be helpful for people who practise IC and are travelling abroad. The travel document offers information on the products the patients carry, for example, for bladder management, and contains contact details of the healthcare provider should a customs employee have any queries.

An example of a medical travel document for patients can be found in:

Appendix K Medical travel document for patients

| Recommendations | LE | GR |

| Ensure patients and caregivers have access to appropriate educational resources and materials [121, 127, 137] | 4 | C |

| Assess the caregiver’s general health, dexterity, motivation, understanding, and availability to undertake IC [118] | 4 | C |

| Ensure that the patient/caregiver understands the basic anatomy and function of the urinary system [141] | 4 | C |

| Ensure that the patient and/or caregiver has a clear understanding of the patient’s relevant urological condition and why they require IC [70] | 4 | C |

| Ascertain the motivation of the patient [58] | 4 | C |

| Investigate the need for special supportive devices [58] | 4 | B |

| Offer support to patients and/or caregivers to help them overcome any initial resistance to IC [111] | 4 | B |

| Counsel the patient and caregiver to express any psychological issues about the caregiver performing such an intimate procedure [135, 138, 139] | 4 | C |

| Advise patients to take a medical travel document in case they are travelling abroad | 4 | C |

8.4 Patient and caregiver education – why, who, when, where, how and what

There is a lack of agreed standards for patient and caregiver education on IC, and only properly trained nurses should provide teaching. A recent consensus meeting on this issue recommended that all healthcare facilities should have an evidence-based guideline for members of the healthcare team as they proceed with teaching patients and their families about the steps in IC. [142] The following sections describe the recommendations from the European Association of Urology Nurses panel members.

Why

The purpose of education is to empower patients and caregivers to enable them to have more control and to ease problem-solving. Education needs to be directed towards patients and caregivers.

Who

When it is not possible for patients to carry out IC, the procedure can be taught to an appropriately trained caregiver. Health professionals need to counsel patients and caregivers regarding:

- potential benefits and difficulties with this method of bladder management

- knowledge and skills required to perform the procedure

- commitment required to carry out IC on a regular basis

- potential lifestyle adjustment

Often patients feel more at ease during a learning session when supported by their partner or carer. This can be valuable when patients’ private circumstances form an obstacle to accepting and feeling comfortable with IC, and the patients have feelings of inferiority or are worried about their sex life.

When

Patients must be physically and emotionally ready to learn because all types of learning require energy. Patient motivation and previous learning experiences are relevant. Nurses need to be sensitive to the patients’ wishes and needs and be prepared to use a variety of educational strategies. O’Connor (2005) [143] has described the importance of self-care in teaching stoma management skills. This can also be applied to IC education. Sometimes an intermediate step must be taken, in which a caregiver or healthcare professional performs the IC for a short time.

Where

Teaching IC may be carried out in the patient’s home or in hospital. The patient’s privacy is paramount in either location. [111, 112]

How

Educators should demonstrate calmness and provide praise and encouragement. It is important to give the patients and caregivers feedback and provide reassurance. [111]

Encourage the patients and caregivers to handle the equipment first and talk through the procedure before demonstrating the technique because this aids the learning process.

Consistent teaching methods and modelling of desired behaviour increase patients’ and caregivers’ technical skills and satisfaction, so patients and caregivers are ready to carry out IC successfully outside the hospital. [144]

More than one appointment with the patients and caregivers may be necessary to allow time for them to assimilate the information given before they can give full informed consent to the arrangement. [140] The wishes of patients and caregivers need to be considered. [145] It is important that neither the patients nor the caregivers feel coerced into performing a procedure with which they feel uncomfortable. [145] Respect for the cultural and religious beliefs of patients and caregivers also needs to be considered. [146]

What

There are many things that patients and caregivers need to know before they can perform the IC procedure confidently and safely. For this purpose, a checklist is provided. This is intended to assist healthcare professionals to check whether all the information about IC that needs to be given to the patients has been provided.

The checklist for patient information can be found in: Appendix A: Checklist for patient information

Patients need:

- verbal explanation of IC

- practical instruction in the procedure

- written information

- instructional video, if available.

Fig. 17 Verbal explanation of IC

(Courtesy of Manchester Royal Infirmary, UK)

Written information

Pretreatment information should be supplemented by booklets (preferably non-commercial), where all topics are explained textually and clarified with relevant anatomical pictures and other patients’ experiences. Digital information can be found on websites of suppliers, hospitals, and patient organisations. Preferably, the information should be written in plain language. [135, 137]

All verbal information should be reinforced with written information that the patients and caregivers can keep and consult.

Choice of technique and material

It is important that healthcare professionals enable patients to make an informed choice when choosing the best method and product for their individual needs. [114, 140] For more information about the choice of technique and material, refer to Sections 9.1 and 9.2.

Supply and reimbursement of catheter equipment

Reimbursement differs in European countries because each has its own healthcare system and insurance. Some patients are not reimbursed for their products and cost must be taken into account when recommending appropriate products. Nurses should be aware of their national rules for reimbursement. Some products are not available locally. Storage and reuse of catheters might in some countries be a deciding factor in patient choice. Increased risk of complications and cost of treatment may offset the advantages of catheter reuse. [140]

Changes in urine colour and smell

Patients need to be aware of possible changes in the colour and smell of urine, due to what they have eaten, drunk, breathed or been exposed to.

| Recommendations | LE | GR |

| Ensure that healthcare professionals are proficient in the skills and teaching of IC | 4 | C |

| IC should be taught by an appropriately experienced nurse | 4 | C |

| Individualise teaching for the patients and their caregivers [125] | 4 | C |

| Use consistent teaching methods and modelling of desired behaviour to increase patients’ and caregivers’ practical skills and satisfaction | 4 | C |

| Develop a relationship and environment that encourages and supports patients towards self-management of long-term bladder conditions [111] | 4 | B |

| Empower patients and caregivers to take an active role in catheter management [135] | 4 | C |

| Provide verbal explanation of IC and sufficient time for practical instruction of the procedure to the patients and caregivers | 4 | C |

| Ensure that all verbal information is reinforced with written information to help the patients and caregivers learn the procedure | 4 | C |

8.5 Ongoing support and follow-up

Integration of IC into everyday life can be difficult. The patients and caregivers require close ongoing support and follow-up. [140, 145, 147] However, only half the patients receive these. [135] It is important to give the patients contact details to access professional help should they require it. It may also be helpful for them to be given the contact details of any available support networks for patients and caregivers.

Following tuition in IC, patients should be offered an early review by a healthcare professional to ensure that they are successfully performing the procedure, and to offer help with any difficulties that they may have experienced. [58, 118, 121, 146, 148] A record of catheterisation practice is essential to assess adherence and compliance. [45] Follow-up review can be by telephone or during consultation at a clinic. [135] In some cases, it might be preferable to have home visits by community nurses to resolve problems and improve compliance in the home setting. [149] To facilitate the evaluation, a voiding diary can be used (see Appendix I: Voiding diary).

Material to take home from the hospital

When patients leave the hospital to continue IC at home, they need to be given a sufficient supply of catheter products, lubricants (if required), bags and accessories for the initial period, which varies depending on local policy.

| Recommendations | LE | GR |

| Provide ongoing social support (by consultation/telephone) to improve QoL [121, 140, 145, 147] and prevent complications | 2a | B |

| Assess patient adherence by keeping a log of catheterisation practice, other relevant aspects and IC cessation. [58] | 4 | C |

| Explore patient-perceived signs and symptoms of UTIs during follow-up [150] | 4 | C |